What Is the Core Message of Zen and the Art of Motorcycle

:focal(6245x4415:6246x4416)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/76/e1/76e140f8-ccda-466f-bd0a-0d4a0f706628/oct2020_f01_prologue.jpg)

Reading Robert Pirsig'southward clarification of a route trip today, one feels bereft. In his 1974 autobiographical novel Zen and the Art of Motorbike Maintenance, he describes an unhurried pace over two-lane roads and through thunderstorms that take the narrator and his companions past surprise as they ride through the North Dakota plains. They register the miles in subtly varying marsh odors and in blackbirds spotted, rather than in coordinates ticked off. Most shocking, at that place is a child on the back of one of the motorcycles. When was the last time you saw that? The travelers' exposure—to bodily hazard, to all the unknowns of the road—is absorbing to present-day readers, particularly if they don't ride motorcycles. And this exposure is somehow existential in its significance: Pirsig conveys the experience of existence fully in the world, without the mediation of devices that filter reality, smoothing its crude edges for our psychic comfort.

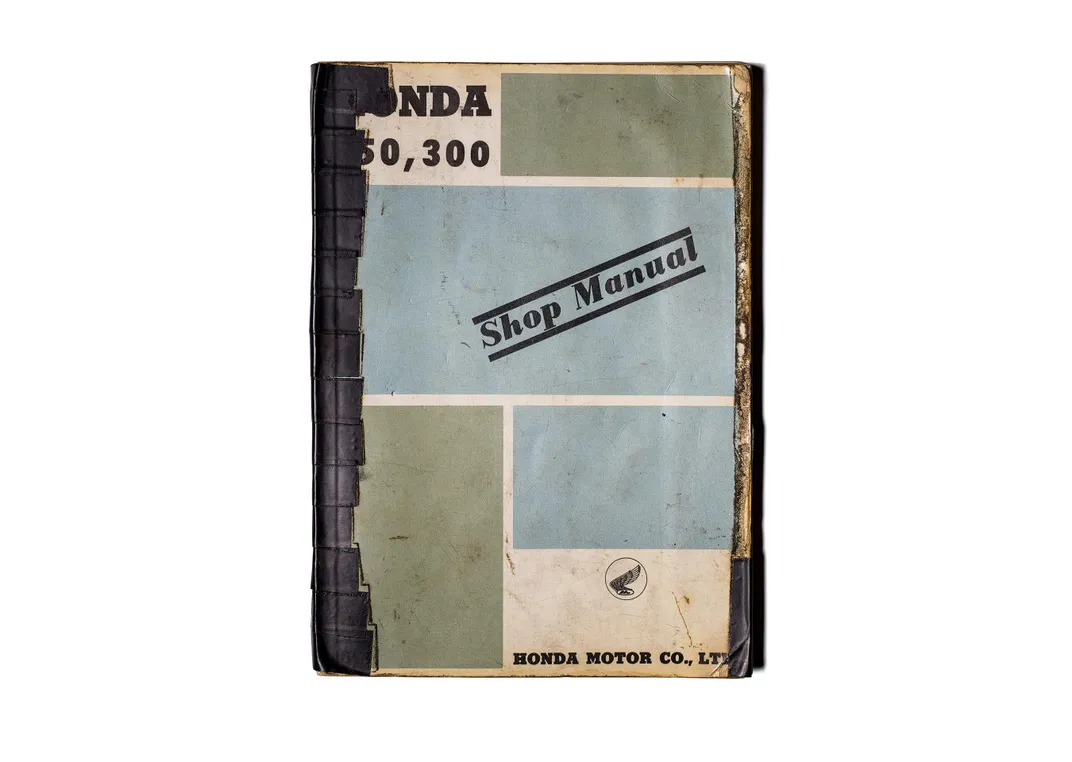

If such experiences feel less available to us now, Pirsig would not be surprised. Already, in 1974, he offered this story equally a meditation on a item way of moving through the world, ane that felt marked for extinction. The book, which uses the narrator's route trip with his son and ii friends as a journey of inquiry into values, became a massive best seller, and in the decades since its publication has inspired millions to seek their own adaptation with mod life, governed past neither a reflexive aversion to technology, nor a naive faith in information technology. At the heart of the story is the motorcycle itself, a 1966 Honda Super Hawk. Hondas began to sell widely in America in the 1960s, inaugurating an abiding fascination with Japanese pattern amongst American motorists, and the company'southward founder, Soichiro Honda, raised the thought of "quality" to a quasi-mystical condition, coinciding with Pirsig'southward own efforts in Zen to clear a "metaphysics of quality." Pirsig'south writing conveys his loyalty to this auto, a relationship of care extending over many years. I got to piece of work on several Hondas of this vintage when I ran a motorcycle repair shop in Richmond, Virginia. Compared to British bikes of the same era, the Hondas seemed more than refined. (My writing career grew out of these experiences—an attempt to articulate the human chemical element in mechanical work.)

In the commencement chapter, a disagreement develops between the narrator and his riding companions, John and Sylvia, over the question of motorbike maintenance. Robert performs his own maintenance, while John and Sylvia insist on having a professional do it. This posture of non-interest, we soon larn, is a crucial element of their countercultural sensibility. They seek escape from "the whole organized bit" or "the arrangement," as the couple puts it; technology is a death forcefulness, and the point of hitting the road is to leave it behind. The solution, or rather evasion, that John and Sylvia hit on for managing their revulsion at technology is to "Take it somewhere else. Don't take it here." The irony is they notwithstanding discover themselves entangled with The Motorcar—the one they sit on.

Zen and the Fine art of Motorbike Maintenance

A narration of a summer motorcycle trip undertaken past a father and his son, the book becomes a personal and philosophical odyssey into fundamental questions of how to live. The narrator's human relationship with his son leads to a powerful self-reckoning; the craft of motorcycle maintenance leads to an austerely cute process for reconciling science, religion, and humanism

Today, we oft use "technology" to refer to systems whose inner workings are assiduously kept out of view, magical devices that offer no apparent friction between the self and the world, no demand to master the grubby details of their operation. The industry of our smartphones, the algorithms that guide our digital experiences from the cloud—it all takes place "somewhere else," just equally John and Sylvia wished.

Yet lately we take begun to realize that this very opacity has opened new avenues of surveillance and manipulation. Big Tech now orders everyday life more deeply than John and Sylvia imagined in their techno-dystopian nightmare. Today, a road trip to "get away from it all" would depend on GPS, and would prompt digital ads tailored to our destination. The whole excursion would be mined for behavioral data and used to nudge united states of america into profitable channels, likely without our even knowing it.

We don't know what Pirsig, who died in 2017, thought of these developments, as he refrained from almost interviews after publishing a second novel, Lila, in 1991. But his narrator has left u.s.a. a way out that can be reclaimed past anyone venturesome enough to try information technology: He patiently attends to his own motorbike, submits to its quirky mechanical needs and learns to empathise it. His way of living with machines doesn't rely on the seductions of effortless convenience; information technology requires us to get our hands muddy, to be self-reliant. In Zen, we come across a man maintaining direct appointment with the earth of material objects, and with it some measure out of independence—both from the purveyors of magic and from cultural despair.

brookshirehobbiregrato.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/robert-pirsig-zen-art-motorcycle-maintenance-resonates-today-180975768/

Post a Comment for "What Is the Core Message of Zen and the Art of Motorcycle"